With the 46th anniversary of the Portuguese Revolution of the 25th of April 1974 upon us, now is a good time to reconsider the life and work of Zeca Afonso.

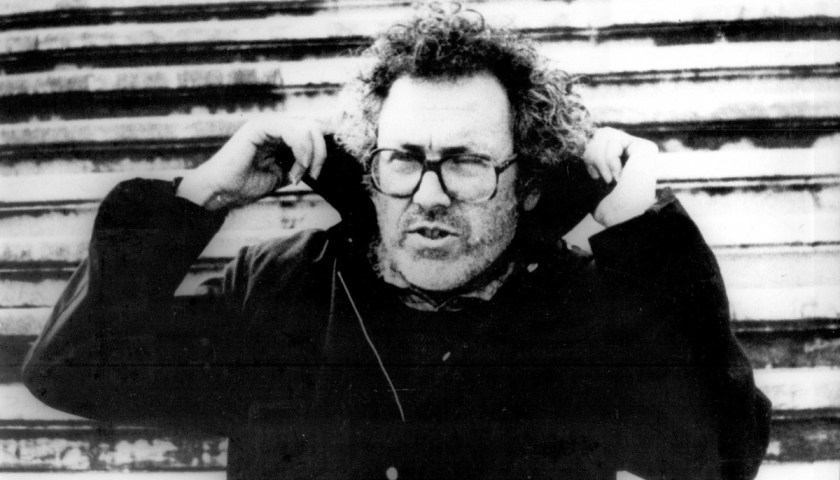

Zeca Afonso (full name José Manuel Cerqueira Afonso dos Santos) is one of the most influential singer / songwriters in 20th century history. He can be fairly compared to Bob Dylan, John Lennon and Mikis Theodorakis of Greece as a political musician of the left. But there is one great difference - the cause he was fighting for - the end of the Portuguese dictatorship and the end of the country's colonial wars, succeeded.

This may be why in Portugal they do not call such singers "protest singers". Instead they are called "singers of intervention" - cantores de intervenção. After all, the singing might just work.

In Zeca's case it certainly did. It is not just supposition that he had an influence on the course of events. The troops fighting Portugal's colonial wars were indeed listening to and playing his songs. Here's an example (it's also an example of Zeca singing in the Coimbra style).

José Zeca Afonso "Traz outro amigo também"

José Zeca Afonso "Traz outro amigo também" (Bring another friend too)

Words and music: José Afonso, 1970

A key feature of Zeca's songs is that their meaning is often not immediately obvious. Portuguese music was heavily censored at this time (as were foreign imports, many of which were just banned outright). Any obvious anti-war or anti-regime message would be stopped, and the perpetrators and those associated with them might well face unpleasant reprisals.

What it means:

Zeca is going along a road. He asks a friend to join him. The wind is getting up. But he's pressing on. He welcomes his friend, and says "Bring along another friend too", even if they are reluctant. For those who stay behind will dream of having been with me. So bring along another friend too.

There is nothing obviously revolutionary in these words. But the meaning of a message is the effect it has on the receiver (a basic tenet of information theory). If the receiver has enough contextual information they will hear the intended message loud and clear.

By 1970, when this song was recorded, Zeca's Portuguese listeners had plenty of information about both him and the state the country was in. So he was clearly talking of doing something about it.

Zeca's journey

Zeca in 1970 was a little over 40 years of age, and had been politically active for at least a decade. He seems to have become radicalised around the time of Air Force General Humberto Delgado's bid to unseat Portugal's dictator António de Oliveira Salazar in the 1958 Presidential election. Salazar was actually Prime Minister not President, but Delgado had said he would dismiss him if he won the Presidency.

Delgado was defeated despite having strong popular support, and was subsequently murdered by PIDE, the regime's secret police. This was known by 1970 because the murder was committed on Spanish soil, presumably without permission, and Spanish dictator Franco had the murderer, a PIDE agent, put on trial. Recently, in 2016 - long after both Iberian dictatorships had ended, Lisbon's main airport was renamed Humberto Delgado Airport.

Zeca spent the early 1970s effectively in exile in London and Paris. Family connections may have helped him keep out of trouble with the regime. He had also been releasing albums of exceptional quality at a rate of at least one a year since 1968. These included the 1971 Cantigas do Maio, and Venham Mais Cinco, in 1973.

José Zeca Afonso "Venham mais cinco"

José Zeca Afonso "Venham mais cinco" (Give me five more, come on)

Words and music: José Afonso, 1973

There had been a brief relaxation in censorship following the accession to power in 1968 of Marcello Caetano, after Salazar became ill following a blow to the head in a bizarre accident. But the colonial wars continued, and this thaw had well-and-truly ended by the time Venham Mais Cinco came out.

Despite many of the lyrics being coded and obscure, the whole album was banned and all copies in Portugal seized. Zeca was briefly held by the PIDE for 20 days in 1973, but by 1974 he was back performing in public in Portugal.

We mustn't over-dramatise Zeca's role in the revolution that then unfolded. It started out as a purely military coup that required well-coordinated armed trained soldiers to carry out - not civilians, and certainly not a scholarly teacher and songwriter like Zeca, whose true role was to inspire.

But the coup did require a non-obvious signal to set in motion the actions of the young plotters, who were mainly of the rank of captain and below, in barracks around the country. The idea was to have a confederate at a popular state-approved Catholic radio station play a distinctive track around midnight if the plan was going ahead.

Otelo de Carvalho was one of the main organisers of the successful 25th of April 1974 coup, and he commanded COPCON, the Armed Forces Movement's mobile troubleshooting force, in the immediate aftermath.

Otelo is on record as saying he preferred Traz Outro Amigo Também as the signal, because he thought the words highly appropriate and he liked the tune. However, in the event the conspirators decided on Grândola, Vila Morena - which some had just heard Zeca perform live in Lisbon.

It has an obvious military feel so it would stand out from the other music on the broadcast, and had just recently been cleared by the censor, who didn't grasp the usual Zeca double meanings.

José Zeca Afonso "Grândola, vila morena"

José Zeca Afonso "Grândola, vila morena" (Grândola, weather-beaten town)

Words and music: José Afonso, released 1971 (written 1964)

The military feel of Grândola, vila morena wasn't deliberate. Zeca had composed it in 1964 as his take on the long-standing tradition of harmony singing in the Alentejo. This style, Cante Alentejano, typically counterposes two lone male voices to a larger male choir singing in unison. It is usually sung without instrumental accompaniment, or with minimal accompaniment. Though the singers might beat their feet, Cante Alentejano doesn't normally sound much like a march.

Zeca's version is now one of Portugal's most famous songs. The words praise the friendliess and equality of the people of Grândola, a small rural town in the Alentejo, the huge sunny farming area that lies to the south of Lisbon across the Tejo river. Morena commonly means brown or brown-haired, but can also mean sun-tanned, swarthy or weather-beaten. Morena has also long been a female first name in Portuguese, Italian and Spanish-speaking countries, deriving from the brunette meaning.

So 20 minutes after midnight in the early hours of the 25th of April 1974 Zeca's Grândola, Vila Morena went out on the radio station Rádio Renascença (Renaissance Radio). Among others in on the plot it was heard by Captain Salgueiro Maia, stationed 40 miles up the Tagus valley at Santarém.

Santarém is now also noted as the birth place of famed fadista Ana Moura (1979-), a child of the peace ushered in by the success of the revolt.

Back in 1974, the Zeca song was the signal for the plotters to march on the government in Lisbon. Traz Outro Amigo Também was sung later on the night, as the rebels moving towards the capital encountered other armed units who didn't know what was going on, and successfully persuaded them to join in the advance.

Only 18 hours later, with an enlarged force at his disposal, Captain Maia was negotiating directly with Marcelo Caetano, Salazar's successor as Portuguese dictator.

Caetano was holed up in the headquarters of the military police (GNR) in central Lisbon. Once the dictator had surrendered (to General António Spínola), Captain Maia ended up personally driving him away in an armoured personnel carrier to protect him from the civilian crowds that had flocked onto the streets. Caetaano died six years later in exile in Brazil. Overall the Portuguese revolution of 1974 involved remarkably little bloodshed in Portugal itself.

The life of Dr José Zeca Afonso

(2 August 1929 – 23 February 1987)

Revolutionary, singer/songwriter

Jose "Zeca" Afonso dos Santos was born in 1929, in Aveiro, near Porto in North Portugal. His father worked as a colonial judge, and the young Jose was brought up in a mixture of Africa (both Mozambique and Angola) with his parents and in Portugal, with various relatives. He attended secondary school in Coimbra, and then went on to the University of Coimbra. Zeca rapidly became known as a good musician in what - then as now, is a very musical university, and that prestige to some extent protected him from the bullying or hazing that was then endemic.

In the earliest Zeca recording he sings clearly in the Coimbra style, with head back and putting great emphasis on the words in a clear declamatory manner. His first records in 1953 were under the name Dr Jose Afonso. Later on his guitar arrangements became more complex, and he worked with musical collaborators who were more skilled on the instrument than himself. Later still he would introduce African elements, with both voice chants and drumming.

During much of this time he supported himself by working as a teacher, though he was banned from official posts after 1967, for his political activities. After the revolution of 1974 Zeca became even more actively political on the left. But he refused offers to join parties or take up office. He saw himself as having a continuing role to speak out as a revolutionary artist against the defects of the new as much as the old regime.

Throughout his life Zeca Afonso had never been particularly fit. Indeed his compulsory military service between 1953 annd 1955 saw him returned to Portugal from Macau on health grounds. In 1982 he was diagnosed with an incurable form of motor neurone disease. He continued to work and compose new material, but finally died in 1987, at the age of 57. Some 30,000 people attended his funeral.

Since his death his work continues to be performed, and on anniversaries events are staged that keep his reperoire alive. During his life Zeca Afonso composed several hundred songs. This legacy is recognised within Portugal as forming part of the country's extraordinary musical heritage.

But as a revolutionary Zeca surely saw himself as belonging also to a wider class, a wider struggle, a wider humanity. In that he was less successful. He is unfortunately an almost purely Portuguese figure. Like other Portuguese artists of outstanding talent he is still not widely known or appreciated outside Portugal.

José Zeca Afonso "Menina dos olhos tristes"

José Zeca Afonso "Menina dos olhos tristes" (Girl with the sad eyes)

Music and voice: José Afonso, 1969

Words: Reinaldo Ferreira

Guitar (viola): Rui Pato

This is a classic anti-war song. Normally as well as composing and singing Zeca also wrote the words, and sometimes played guitar - but on this occasion he did neither. He set music to an existing poem, and then worked with a virtuoso guitarist. This works very well - the arresting guitar part provides contrast to Zeca’s intense, eventually almost desperate, voice.

What it's about: the girl is waiting for her soldier to come back from overseas. But he won't - the war has taken him.

Different versions of Zeca Afonso's Menina dos Olhos Tristes - YouTube playlist of several versions by different artists of “Girl with the sad eyes”, starting with the one above sung by Zeca.

See also on this site

Portugal's Eurovision entry 1974 - consolation prize: Revolution!

This is about the other song used to signal the start of the April 1974 coup, Paulo de Carvalho's "E depois de adeus" (And after goodbye). It went out earlier and was the trigger for the junior officers to come out into the open and start taking over their bases. There is also more on how the 25th of April unfolded.

Cante Alentejano - traditional male voice choirs of southern Portugal

The style Zeca's song Grândola, Vila Morena was inspired by.

Further information

Associação José Afonso Has the words of all Zeca's songs (in Portuguese) along with much other material.

Your thoughts are welcome. Comments powered by Talkyard.