Timeline

Romans

218 BC The Romans arrive in the Iberian peninsula

Their initial motive is to dislodge the Carthaginians, who had an expanding military presence on the south and east coasts at the time of Hannibal in the second Punic war. Defeating the Carthaginians in Iberia was to take the Romans 12 years.

The Romans then set about colonising the whole peninsula, both Spain and modern Portugal. This was to take 200 years to complete, and involved the Republic's two top generals, Julius Caesar and Pompey the Great, at various stages. It was a considerable undertaking, involving at its maximum seven Roman legions in the field at the same time.

The Romans bring Latin. Modern Portuguese is basically still Latin - optimised over the years for poetry and song.

Ângela Silva Rodrigo Leão "Carpe diem"

Ângela Silva sings composer Rodrigo Leão's "Carpe diem" (Seize the day) in Latin

This is a hymn to love made up of common Latin phrases. Though Latin is not widely understood now, Portuguese singers don't have much trouble with the pronunciation and phrasing.

139 BC Death of Viriatus - resistance begins to fade

Viriatus (Viriato in Portuguese) is the Portuguese equivalent of Vercingetorix in France and Boudica or Caratacus in Britain. Resistance to the Romans was most intense in the upper Douro valley, on both the Portuguese and Spanish sides of the modern border.

Local hero Viriatus, hailing from somewhere in the Douro valley, is celebrated today in both countries. After numerous victories Viriatus was finally killed by treachery (like that other famous enemy of Rome, Arminius in Germany).

26 to 19 BC Roman conquest completed

The Romans defeat the last remaining resistance, in the Asturias mountains in northern Spain. This is during the reign of the first emperor Caesar Augustus (Octavian), who turned up in person (bringing elephants!) for part of the campaign.

Rome was partly motivated to complete its conquest of Iberia for military reasons - subduing the whole peninsula would eliminate potential reservoirs of resistance. But another factor was that the far north of Iberia, in both modern-day Portugal and Spain, contains gold. The Romans exploited gold mines here (and silver further south) as soon as they got control.

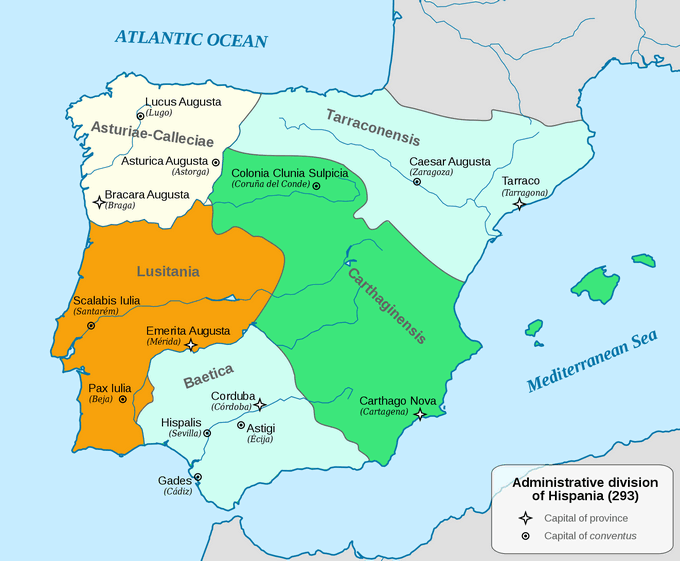

Portugal in Roman Iberia

The Romans divide the peninsula up into several provinces, which changed a bit over time.

Eventually most of Portugal south of the Douro river came under the Province of Lusitania. Portugal north of the Douro ended up coming under the Roman province of Gallaecia (aka Callaecia before the letter G came into common use), which extends right up to modern-day Spain's northern sea coast.

This division makes some sense in that the north has a colder, wetter Atlantic climate and is more mountainous. The Romans were principally interested in it for strategic reasons and for the mines it contained. When it came to agriculture they wanted land able to support large scale farms operated with slaves (latifundia), producing crops they were familiar with. Lusitania, with its more Mediterranean climate and flatter land, especially south of the Tagus, fitted the bill better.

Lisbon was then called something which to Roman ears sounded like Olisipo (surely not Lisboa?). It was expanded and given full Roman municipal status under the name Felicitas Julia Olisipo (Felicitas meaning happiness or prosperity, Julia being the dynastic name of the imperial family granting the title). The inhabitants became Roman citizens.

But the province of Lusitania was ruled not from Lisbon but from Emerita Augusta, a city established for retired soldiers from the Roman legions. Now called Mérida, it is across the modern-day border in western Spain on the Guadiana river. This flows into Portugal, through Alentejo and Algarve to the sea. Under the Romans both these regions became very agriculturally productive (mostly wheat, vines and the fermented fish sauce known as garum).

North of Lusitania, in Gallaecia, the Romans also expanded two other towns important to the future of Portugal - Braga (Bracara Augusta), and the sea port then known as Cale. This became Portus Cale in Latin. The first part of the name has stuck - the town is now known as Porto in modern Portuguese (or Oporto in English). But the whole Roman name Portus Cale is the origin of the name Portugal - eventually given to the entire country.

4th Century Christianisation of Portugal

Bishoprics are established at Braga, Lisbon, Évora and Faro.

Barbarians

409 Barbarians arrive and some settle

With the decline of the Roman empire in the west the period of the mass migrations of peoples begins.

Suevi (possibly related to modern-day Schwabians in south Germany) and Alans (possibly related to modern-day Ossetians on the Russia-Georgia border area) sweep in. Both these groups settle, the Suevi mainly in Gallaecia and the Alans further south over much of Lusitania. Other barbarian groups such as the Vandals largely by-pass Portugal.

585 Visigoths capture Iberia

More Germanic invaders arrive. The Visigoths are militarily very successful, and also settle. But they have left much less of a trace apart from a few castles than the earlier Suevi and Alans. This may be because they were a small warrior elite who intermarried and soon got absorbed. But another reason is that the Visigoths were already heavily Romanised and partly Christianised by the time they got to Portugal, and so fit in with existing customs and institutions, causing less disruption. And a warrior class they are almost wiped out in the next phase of Portuguese history.

Moors

711 Moors begin conquest of Iberian peninsula

The Muslim "Moors" were a mixture of an Arab-speaking military, commercial and land-owning elite, and large numbers of Berber-speaking troops from north-west Africa. The Moors landed first in Gibralter, and within seven years have conquered most of Iberia including Portugal. Then moved onwards into France, where they were eventually turned back, starting at the Battle of Tolouse (721).

722 Covadonga - first significant defeat for Moors in Iberia

A Visigothic nobleman called Pelagius had set up a small kingdom in the mountainous coastal region of northwest Iberia, north of Léon in modern Spain. Though the battle itself may have been a small skirmish, subsequent victories by Pelagius had the effect of establishing the Kingdom of Asturias as independent from Moorish rule. This was the base from which the Reconquest could start. Indeed, the Reconquest is conventionally dated from the Battle of Covadonga (722 or sometimes 718) to 1492, the fall of Granada, in Spain, or 1249, the fall of Faro, in Portugal.

Reconquest

868 Christians regain Porto

Porto is recaptured by Christian forces led by the kings of Léon and Asturias.

Latin languages return with the Reconquest.

The Moors probably spoke Arabic at the elite level and Berber among the bulk of the north African troops. MozArabic means something like "not-Arabic", "faux Arabic" or "Arabised non-Arab", and was the language of the subject population. Fragments have been recovered from quotes and refrains in Arabic and Hebrew poetry, and it is clearly a Latin language.

But as the Reconquest proceeded, Arabic, Berber and MozArabic gave way to Latin languages from the Christian north.

Credit: The original creator of the animated language map was Alexandre Vigo at Galician Wikipedia. I have slowed the animation and reduced the filesize. Istobe licence CC BY-SA 3.0

1147 Lisbon and Santarém recaptured from Moors

Lisbon is retaken from the Moors after a 17-week siege. First Santarém further up the Tagus valley is taken, then Lisbon itself. Afonso is assisted by a crusader fleet, including Templar knights and Welsh archers.

1162 Christians move south of the Tagus river

Beja and Évora, strategic towns in modern-day Alentejo, are next to be recaptured from the Moors. Most of the population and productive land of Portugal is now under Christian control.

1249 Last muslim stronghold falls in the Algarve

Faro, the last remaining Moorish holdout, is recaptured by forces of King Afonso III.

First African conquests

Age of Discoveries

1415 Beginning of the Age of Discoveries

Fausto Bordalo Dias "O barco vai de saída"

Fausto Bordalo Dias "O barco vai de saída" (The boat is setting out)

Fausto realises that, despite the enormous dangers, going on a voyage would be exciting to many stuck in rural, feudal Portugal. You could also escape your troubles back home. Luís de Camões (1524 to 1580), the great soldier/poet of this period, seems to have left Portugal to escape the fallout from three of the most popular troubles - indiscreet affairs, fighting and debts.

1419 Uninhabited Atlantic island Madeira discovered

This heavily wooded (madeira means wood) mountainous volcanic island has plenty of rainfall and lots of productive microclimates, and is soon settled by the Portuguese. They clear many of the trees to grow grain, which is exported to Portugal's north African enclaves such as Ceuta. Today Madeira is a component part of Portugal, producing wine and footballers.

1427 Azores islands discovered

Located directly west of Lisbon far out in the mid-Atlantic, these 10 or so volcanic islands are also uninhabited when the Portuguese arrive. With a more temperate climate than Madeira, these islands are also agriculturally productive. Today they are an integral part of Portugal and a big producer of dairy products.

1434 Portuguese finally manage to get past Cape Bojador

This is a headland on the north-west African coast south of the Canary Islands, jutting out from the Sahara desert, and currently disputed territory administered by Morocco. In the 15th century it was a major obstacle to navigation, with the problem being currents, shifting shoals and a prevailing south-west wind. The Arabic name for Bojador means "father of dangers". It took the Portuguese 15 attempts, with the Portuguese mariner Gil Eanes, a member of the household of Henry the Navigator, finally managing it.

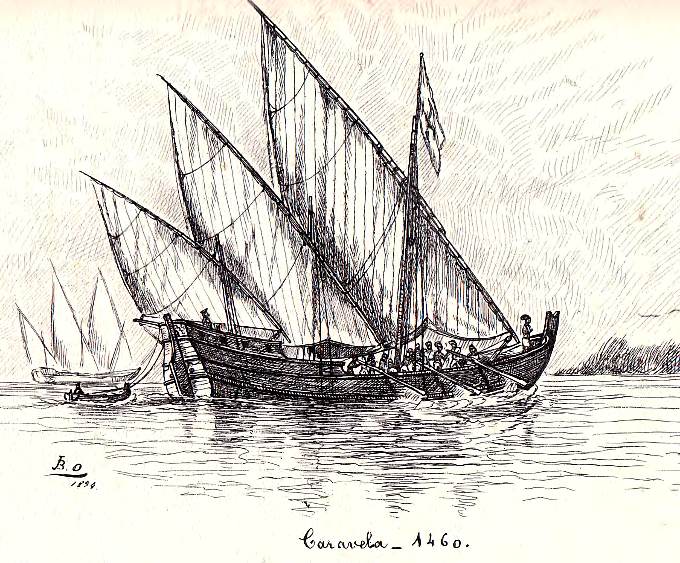

1430 to 1450s Portuguese develop caravel ship for exploring

The difficulty encountered getting round Cape Bojador was one of the reasons for the development of the Caravel (caravela in Portuguese). It was a new type of small, light ship, better suited for exploring than the square-rigged Barca used by Eanes.

The caravel had a shallow draft, allow it to go closer inshore and up rivers. It was light enough to be rowed if necessary. But its main distinguishing features were its triangular-shaped lateen sails, mounted on long sloping spars attached to two or three masts. This type of sail forms an aerofoil like modern sails, allowing the caravel to sail closer into the wind unlike the square-rigged vessels normally used for long-distance sailing at the time. And the caravel's sails could be handled by a small crew. Carrying just 20 or 30 men meant it could stay at sea longer with the water and food on board.

The Portuguese used these specialised small ships to explore along the coast and up rivers, and also to venture far out to sea to map out the seasonal pattern of the trade winds, which they were beginning to understand. Armed with this knowledge larger square-rigged ships, capable of carrying more cargo, armaments and men, could then go on long oceanic voyages with a much better chance of survival.

1457 Cape Verde Islands discovered

Also very probably uninhabited when the Portuguese arrive.

1470 Portuguese reach islands of São Tomé and Príncipe

These islands deep in the Gulf of Guinea were uninhabited too.

1488 Bartolomeu Dias rounds Africa into the Indian Ocean

Dias not only reach the Cape of Good Hope, but then sailed another 400 miles (650 km) along the south coast of Africa as far as modern Port Elizabeth, landing in Algoa Bay. Dias had set out with two caravels and a larger expendable support ship, which he had used to set up a support camp before embarking in the caravels for the final push on a long looping course round the tip of Africa.

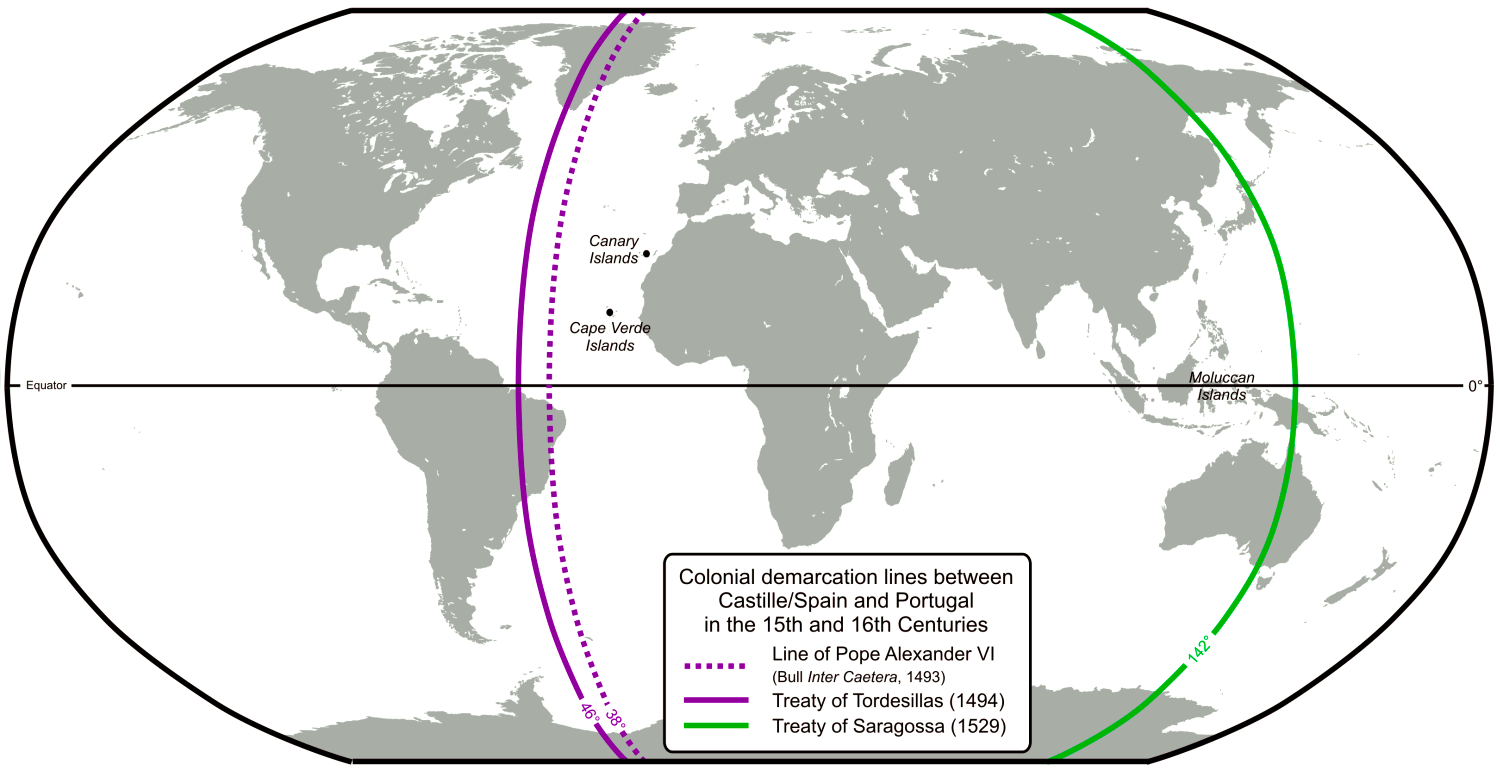

1494 Treaty of Tordesillas divides world between Spain and Portugal

The agreement was sanctified by the papacy, and largely stuck - or at least prevented major war. Other countries, especially Protestant countries after the Reformation, but also France, largely ignored it.

Spain got to the west of the purple line running through the Atlantic, Portugal to the East - thus all the landfalls reached via the Cape of Good Hope into India, China and beyond.

The green line is the corresponding meridian in the Pacific, but what actually happened was more confused. The Portuguese traded as far east as Japan and the so-called Spice Islands or Moluccas (now in eastern Indonesia). But the Spanish moved into the Philippines, well to west of the supposed line. However, the Portuguese also moved west over the line in Brazil, exploring far into the interior. This wasn't all sorted out till 1750, when a new treaty came into effect.

Eastern spice empire

1498 Vasco da Gama takes large fleet to open up trade with India

Ten years after Dias pioneered the route the Portuguese make their well-prepared move in force into the Indian Ocean. The Portuguese knew that Muslim traders dominated the routes taking goods from India via the Red Sea and overland caravans through Egypt to the Mediterranean. They expect resistance and get it.

1503 Portuguese capture Cochin, a major Indian spice port

This is Portugal's first major gain in Asia, and the first European colony in India. Cochin (now Kochi in the India state of Kerala) is on the south-west coast south of Goa, and the centre of a major spice-producing region known as the Malabar Coast.

1510 Portuguese capture Goa on the Indian coast

Goa is in a better defensive position than Cochin, and goes on to become the military and administrative capital of all Portugal's Indian and wider Asian possessions into the 20th century.

1511 Portuguese navigators reach China

1543 Portuguese arrive in Japan

They were the first Europeans to do so and set up a successful trade mission. Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier (probably a Basque name, born in the Kingdom of Navarre, now a Catholic saint) arrives in 1549. The Portuguese had an exclusive trade deal with the Japanese for over a century.

Defeat in Africa

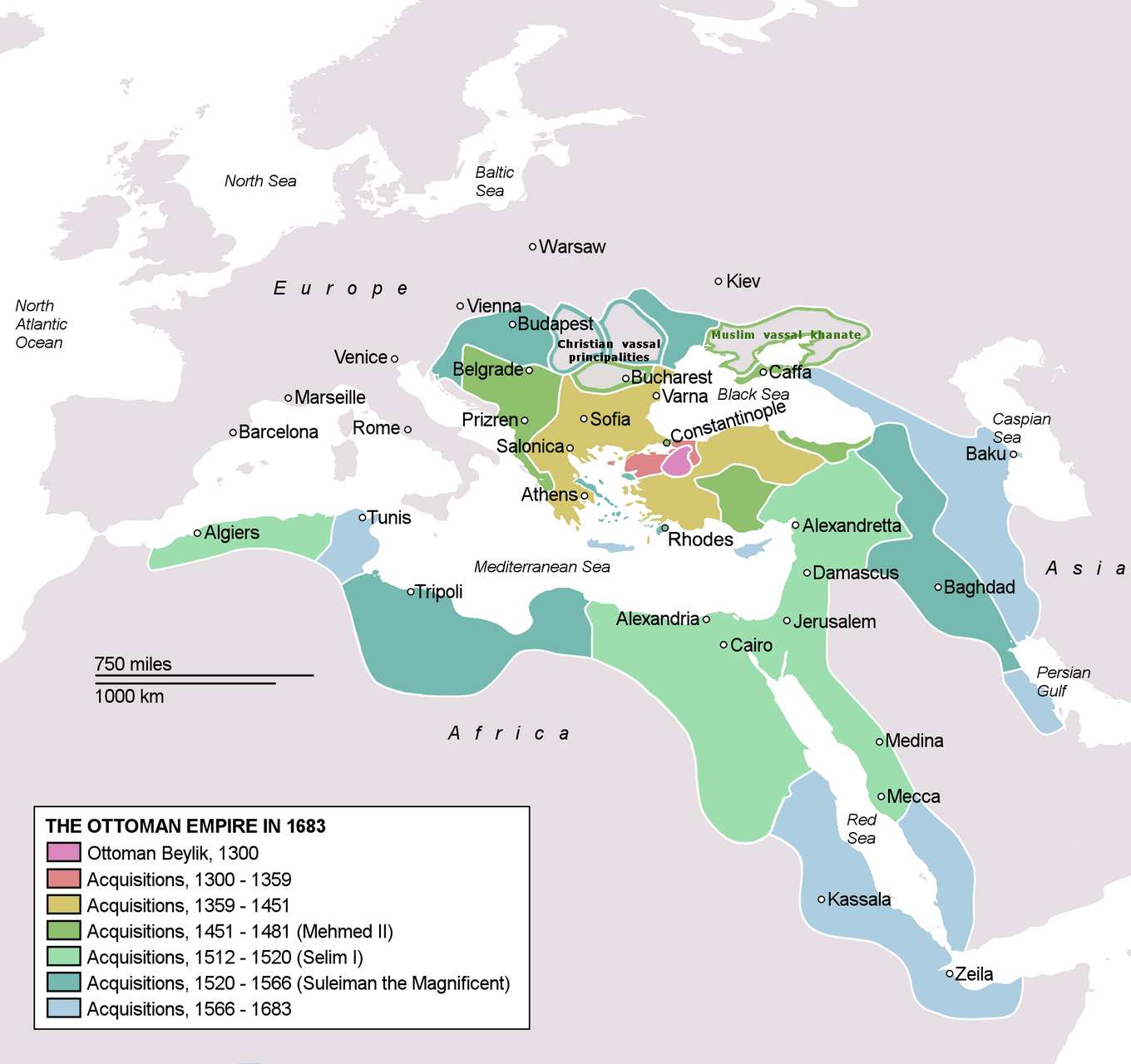

1574 Ottoman Turks capture Tunis from Spain

Developments elsewhere in Europe and north Africa were about to influence Portugal. The Christian Habsburg dynasty, which controlled Austria and Spain and lots of other European territory, had been involved for years in an epic struggle with the Muslim Ottoman empire, centred in Turkey.

In the long-running Ottoman–Habsburg wars the Ottomans were winning in the Balkans, having captured much of Hungary and beseiging Vienna itself, though unsuccessfully, in 1529. From the 1550s Ottoman-allied pirates (aka corsairs or Barbary pirates) had been attacking coastal settlements virtually at will around the Mediterranean (mostly to capture slaves). But after taking Cyprus, the Ottomans had recently suffered a major naval defeat at the battle of Lepanto (1571).

In north Africa the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs had allied with local Muslim forces in Tunisia in an on-off war with Algiers, an Ottoman-backed pirate-centre. But in 1574 the Ottomans decisively defeated Spain and its Tunisian allies, taking Tunis. They went on to install a Turkish-speaking regime complete with Janissary troops, and made Tunisia a full province of the Ottoman empire.

Viewed from Portugal, there was no longer much of a buffer between their area of interest and expanding Ottoman power. With their traditional Berber enemies directly to the south of them, and the Ottomans coming from the east, the security of the Portuguese (and Spanish) reconquest looked somewhat shaky.

It is in this context that the apparently rash military intervention of the young Portuguese king, Sebastian, in Africa begins to make a bit more sense.

1578 King Sebastian meets with disaster in Morocco

Sebastian (Sebastião) undertakes a huge but ill-advised expedition to conquer Morocco, directly south of Portugal in north Africa. Most of the Portuguese army and nobility is killed or captured. The 24-year old king dies on the battlefield at Alcácer Quibir. Back in Portugal, his elderly, celibate uncle Henrique, takes over as King Henrique 1.

As a Cardinal and Archbishop in the Catholic church, Henrique requires permission from the pope to marry and attempt to produce an heir. This is not forthcoming. When Henrique then dies - in 1580 at the age of 68, the house of Aviz, and Portugal, is faced with a succession crisis.

1580 Death of Camões and end of Portugal's first Golden Age

With the ending of the Avis dynasty and the death of Portugal's national poet Luís de Camões in the same year, 1580 is often taken to signify the end of Portugal's first "Golden Age". The 10th of June, the day of Camões' death (probably from plague), is now marked by the public holiday Portugal Day - full name in Portuguese Dia de Camões, de Portugal e das Comunidades Portuguesas.

Spanish take over

1580 Spanish take over Portugal

Philip II of Spain, a member of the powerful Europe-spanning Habsburg dynasty (casa de Habsburgo in Portuguese), had a claim to the Portuguese throne through his mother. And he sent his armies to Lisbon, now bereft of much of its military resources, to enforce it. With Lisbon in the hands of the Spanish, the Portuguese Cortes (assembly of powerful nobles, clerics and merchants) met in Tomar in 1581 and agreed to Philip's claim, on condition that Portugal and its empire is not incorporated into a unified Spain.

Instead it is ruled as a separate Habsburg royal possession. This brought Portugal into the Spanish fold with relatively little opposition. For the next 60 years Portugal is run from Spain but with a separate bureaucracy, in both Portugal itself and its colonial possessions. On the plus side Portugal is now part of the continent-wide Habsburg alliance, giving it a probably more competent military leadership against any Muslim incursions than it had under the indigenous House of Aviz. On the negative side it was drawn into other Habsburg conflicts, which were ongoing against the Dutch, English and French.

1588 Spanish Armada a disaster for Portugal

The famous "Spanish" Armada that sets sail from Lisbon to conquer the England of Elizabeth I includes the best ships of the Portuguese navy in among Philip II's giant fleet. When English defenders and storms at sea destroys most of the fleet, the Portuguese ability to defend its far-flung empire and trade routes is fatally weakened.

1588 to circa 1663 Portuguese empire under attack

In the next few decades Portugal's main trade rivals the English, French and Dutch exploit Portugal's weakness whilst it is under neglectful Habsburg rule. In this world-spanning conflict the English and their local allies force the Portuguese from Hormuz in the Persian Gulf in 1622.

But it is the Dutch who especially target Portuguese possessions, in a bid to expand their own trading empire. In Africa the Dutch briefly capture Luanda in Angola, a source of slaves, and succeeded in taking Elmina, an important trading fort in Ghana in 1635. They take the settlement at the Cape of Good Hope in southern Africa off the Portuguese in xxx.

The Dutch periodically blockade but didn't succeed in capturing Goa, the main Portuguese military and trading hub in India. But they do capture the Portuguese bases in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and the Malabar coast of India.

1623 The Dutch attack Brazil, briefly taking the then-capital, Salvador. But they are forced out when a Spanish-Portuguese fleet arrives.

1630-1654 Dutch take over north-east Brazil

The Dutch capture Recife and this time they stay. Recife was at the time the richest part of Brazil. It was the hub of a vast slave-operated sugar-producing region.

The Dutch gradually expanded their Brazilian territory, calling it "Nieuw Holland". This lasted until after Portugal's union with Spain ended.

Independence regained

1640 Birth of Bragança dynasty and start of independence war

A revolt against Spanish rule in Catalonia caused the Habsburg regime in Madrid to instruct Portuguese nobles to recruit troops to help put it down. But it occured to some nobles that a better use of these troops would be to revolt themselves, and re- establish Portuguese independence.

By now Spanish kings had stopped spending time in Portugal, so the opportunities for patronage for nobles unable to afford maintaining a presence in Madrid were sharply reduced. Habsburg stewardship of the Portuguese empire was proving a disaster, so significant commercial interests were also disenchanted with the Iberian union.

As far as the people were concerned, a revolt against increased taxes had already broken out in Évora in 1637, spreading rapidly throughout the south. It had taken Castilian troops to put this down, increasing anti-Spanish resentment.

So there was the basis for a wider national revolt. All it needed was a credible royal leader.

The current head of the powerful Bragança house was 38-year-old João, eighth duke of Bragança. He was the grandson of Catarina, Philip of Spain's main rival to the Portuguese throne back in 1580. In fact Catarina's claim had been arguably stronger than Philip's, though she lacked the military means to enforce it.

This time João had recently been appointed commander of the Portuguese troops destined for Catalonia. So he had the means, and a credible link back via Catarina to the Aviz dynasty of Portugal's Golden Age.

João moved cautiously. But in January 1641 a meeting of the Portuguese Cortes declared him king, as João IV.

It took 28 years of war before Habsburg Spain accepted that Portugal was independent again. But within Portugal, and the wider empire, the restored resident monarchy was able to establish control quickly, and with little bloodshed after the initial coup.

1641 Dutch capture Portuguese base at Malacca

Now in modern Malaysia, the base commanded the Strait of Malacca, a narrow channel separating the Malayan peninsula from the island of Sumatra (now in Indonesia). Then as now this is a major sea route, linking the Indian Ocean to the South China Sea and wider Pacific Ocean. One consequence of the Dutch victory was that Portugal lost the lucrative trade with the nutmeg-producing "Spice Islands".

1641 Portuguese expelled from Japan

A new Japanese regime banned Christianity and expelled the Portuguese traders, who previously had a monopoly on European trade. They are replaced by the Dutch, who agree not to proselytise.

1648 Portuguese expel Dutch from Brazil

The newly re-independent Portugal sends a large military expedition to get back north-east Brazil. This links up with Brazilian plantation owners already in revolt against the Dutch. After several battles the combined Portuguese loyalist forces finally recapture Recife in 1654, and force the Dutch out.

1663 Dutch capture Cochin on Indian Malabar coast

Having failed to capture Goa, the Dutch go after another Portuguese trade asset to its south. Cochin (now Kochi) is a major loss. Portugal's first Indian colony was at the heart of the spice-producing Malabar Coast.

1663 Dutch-Portuguese war ends

The score sheet: Portugal has retained its vital American possession Brazil, and - with Brazilian help, retained its most important African slave source Angola. But elsewhere in Africa it loses a valuable slaving and gold-trading base in Ghana and the strategic harbour at the Cape of Good Hope, which the Dutch take over and begin to settle.

In India Portugal succeeds in retaining its main centre at Goa, but loses control of Cochin and the neighbouring spice-producing region. In China it retains its trading hub in Macau. But elsewhere in Asia it loses heavily to the Dutch, losing control of Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka), the Strait of Malacca and all the Japan trade.

1668 Peace treaty with Spain

Spain recognises Portuguese independence, the Bragança monarchy, and Portugal's overseas possessions. With one exception - Ceuta, Portugal's first African colony. Spain hangs on to this (and is still hanging on in the 21st century, despite Moroccan protests). This is less of a loss for Portugal than it might seem, as Ceuta was cut of from its natural hinterland (held by the Moors), and was dependent on supplies from nearby Spain.

Renewed English alliance

1703 Methuen treaties link Portugal and Britain

Closer military and trade co-operation is agreed between the two countries near the beginning of the reign of Queen Anne in England (1702 to 1714). Portuguese wine is given preferential access to British markets (especially over French wine), while British wool and textiles are accorded similar status in Portugal and its colonies.

The link was to turn out to have long-lasting economic effects, boosting the fortunes of Portugal's wine producing regions, but suppressing the development of an indigenous textile industry.

On the military side, the Methuen treaties saw Portugal, at the time in alliance with France, switch sides. It joined the Grand Alliance of England, Austria (under the Habsburgs) and the Dutch Republic against France and Spain.

And there was a war on. The Methuen agreements were a response to much larger events in Europe.

1703 to 1714 Portugal in the War of Spanish Succession

During the reign of Louis XIV (1643 to 1715) French power and influence grew enormously. This posed a threat to many countries, eventually resulting in a Europe wide war - indeed arguably one of the first world wars as fighting spread well beyond Europe to the Americas, Africa and Asia.

The immediate cause was that the French appeared to be succeeding in a dynastic takeover of Spain. Louis' grandson Philip V had recently taken over the Spanish throne after the death of a childless Habsburg king in 1700. A grand Alliance of Austria (also run by the Habsburg dynasty who wanted Spain back), England and the Dutch Republic sought to block this development in the War of Spanish Succession (1701 to around 1714).

A stronger Spain run on French absolutist lines might seem to threaten Portuguese independence. But until the Methuen treaties Portugal under Pedro II appeared to be siding with France. After the treaties Portugal became a grand Alliance base for both naval forces and the launchpad for a direct land assault on Spain.

Regarding Britain's motives, Louis XIV supported the rival Stuart claims of so-called "Jacobites" against Queen Anne and her likely Protestant successors. The Jacobites were mainly Catholic supporters of James II, the Queen's deposed father, and his son.

1707 Battle of Almansa

Austrian and British forces land in Lisbon, and along with a large Portuguese contingent advance into Spain. Though successful in Catalonia, where the Catalans are backing the Habsburgs not Philip, the Alliance comes unstuck at Battle of Almansa near the Castilian - Valencian border. Spanish and French troops under the command of an illegitimate son of James II inflict a heavy defeat. It is clear Philip will be difficult to dislodge.

Results of the war

The war itself was a huge sprawling affair with fighting in six or seven European countries, North America ("Queen Anne's War"), the Caribbean and even Asian and African colonial possessions. It eventually ended between 1713 to 1715, depending on which of the many belligerents you consider.

The outcomes of most significance to Portugal were a follows. Philip V remained king of Spain but agreed neither he nor his descendants would unite Spain with France. Britain took Gibralter and Minorca (aka Menorca) off Spain. But Spain itself radically centralised and got more efficient under Philip and his Bourbon line.

Catalonia and the rest of Aragon lost their historic autonomy, with Castilian become the only language of government. Portugal's alliance with England and separation from a more Madrid-dominated Spain was confirmed.

1750 Treaty of Madrid

Spain and Portugal agree to replace the 250-year old Treaty of Tordesillas with something that more closely matches what has happened on the ground. Borders roughly corresponding to modern Brazil are agreed, but Brazilian expansion west, north and south towards modern Argentina is stopped.

1755 Great Lisbon Earthquake

Terramoto, Pombal, Jesuits xxx. Tidal wave also hit Algarve south of Lisbon.

1846 Death of Severa, first of the great fadistas

Maria Severa Onofriano de Souza, known as Severa, dies in Lisbon at the age of 26. Severa's life was immediately romanticised and embellished.

Like almost all the early female Fado singers, Severa belonged to a stratum of low-born Lisbon prostitutes and mistresses patronised by upper-class and aristocratic clients. Many stories and songs have been written about her, but little of her own repertoire remains. The practice of female fadistas wearing a black shawl is said to go back to Severa herself.

1867 Death penalty abolished in Portugal

This didn't stop later regimes from killing their enemies, but they did it by other means. Salazar never formally re-imposed the death penalty.

Clash in Africa

1890 British ultimatum

End of Bragança dynasty and Portuguese monarchy

1908 King and heir assassinated in Lisbon

King Carlos and his eldest son - the heir to the throne, were both assassinated on the Praça do Comércio (the big square on the seafront also known as the Terreiro do Paço). The younger son, aged 18, was injured in the arm but survived. He became king immediately, as Manuel II.

One of many wildly different contemporary imaginings of the assassination

The royal family had just returned to Lisbon by boat. They were being driven across the square in a royal coach when the republican assassins, a teacher and a journalist, struck.

The attack followed a period of increasing anti-monarchist agitation, followed by a fierce state crackdown on dissent. King Carlos had dissolved Parliament and was ruling by decree through a strongman prime minister.

1910 The new king abdicates after armed revolt

Rebellious sailors had joined a revolt by some army units and armed civilians. From their ship on the Tagus they shelled the royal palace, in which the King, according to some accounts, was playing cards. King Manuel II leaves Lisbon, and the next day, with the revolt gathering strength and insufficient loyal units rallying round, abdicates and leaves Portugal. Manuel eventually dies in 1932 in exile in England, without an heir.

In Portugal a Republic is declared. This day is now celebrated on October the 5th every year as Republic Day (Implantação da República). The Republican Revolution marks the end of the 270-year old Bragança dynasty and the end of monarchy in Portugal.

1911 Portugal's Republican Constitution

Replacing the king with a President and Prime Minister, it severely reduces the power of the Church and landed aristocracy. Divorce is legalised and workers given the right to strike. A new red and green flag, the one still used today, replaces the predominantly blue and white flag of the monarchy.

But the governments formed during the First Republic, as it becomes known, are weak and unstable. Military revolts, political assassinations and plots to restore the monarchy are common.

Portugal in the First World War

1914 First World War: Germans attack in Africa

In the early stages of World War I, Portuguese colonies in West and East Africa (Angola and Mozambique) come under attack from German territory. Portuguese troops on the ground fight back, while the government in Lisbon - still unstable and divided following the Republican revolution, is indecisive. In alliance with the Union of South Africa and Britain, local Portuguese forces push the Germans out quickly from Angola in the west. But in East Africa the Germans prove hard to stop.

1916 Portugal and Germany officially go to war

Germany officially declares war on Portugal first after Portugal seizes German ships in Lisbon harbour. Fighting continues in East Africa.

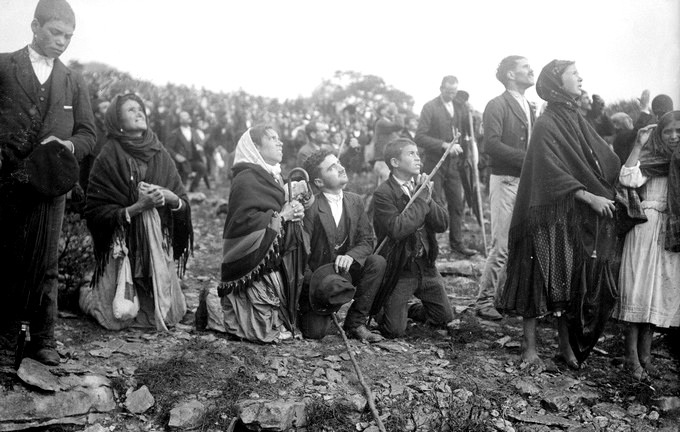

1917 "Miracle of Fátima"

In May, three children looking after sheep in the countryside near Fátima in central Portugal reported seeing a heavenly apparition. This is interpreted by the local church as a genuine vision of the Virgin Mary. Increasingly large crowds assemble in the area, with the apparitions continuing into October.

Newspaper photo of part of the crowd at the final apparition in October 1917

Some commentators have seen this as the Catholic Church demonstrating its ability to mobilise popular support, at a time when the Church's position in Portuguese institutions was under attack from the Republican government. Whatever the status of the visions mobilising them, such popular support can effect real political events.

Fátima has since become a major pilgrimage site, with several million visitors a year. Two of the children were posthumously canonised (made Saints) by the present pope, Francis, on a visit to Fátima in 2017.

1917 Setbacks in East Africa

On the African front, the Portuguese suffered a severe defeat at the Battle of Ngomano (or Negomano) in November 1917, when German forces cross over into Mozambique from what is now Tanzania. They proceed to capture the recently arrived Portuguese force sent to stop them and seize its abundant supplies. The German forces are mostly armed African recruits called Askaris and locally-recruited African porters, with a smattering of German officers and NCOs, all under the leadership of general Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck.

Re-equipped with Portuguese weapons and ammunition captured at Ngomano, they are then able to roam almost at will in Mozambique. They eventually leave in 1918 to attack the British possession of Rhodesia. This German army was still at large at war's end in November 1918. But Mozambique was devastated. Famine and later flu claimed very large numbers of lives - estimates go into the hundreds of thousands. Portuguese prestige in the region suffered irreparable damage.

1918 Disaster for Portuguese army in Flanders

Meanwhile in Europe successive short-lived Portuguese governments had managed by early 1917 to raise an infantry and artillery force of around 60,000 men and sent it to join the fighting in France and Flanders, on the side of the Allies. From the outset it suffered heavy casualties at the hands of the more experienced Germans. And a change of government in Portugal resulted in the the drying up of replacement recruits to make up the losses.

By 1918 Morale among the men in the Flanders trenches is deteriorating, and desertions including among officers increase. Just as mutiny starts to break out the Germans launch a major attack. The Batalha de La Lys (known as the Fourth Battle of Ypres to the British) in April 2018 is a catastrophe for the Portuguese. Their losses from this single engagement were around 400 dead and many more injured (some of them gassed), with over 6,500 taken prisoner.[1]

This very negative experience in World War I probably played a major role in Salazar's later determination to keep Portugal out of World War II for as long as possible.

Rise of the dictatorship

1926 Military coup overthrows Parliamentary government

This had been preceded by several attempted or only partially-successful coups. This time no other military unit came to the aid of the government, so the fall of parliamentary stage of the Republic, was largely bloodless. General Gomes da Costa enters Lisbon to the acclaim of the crowd. By this stage the Republic had few defenders. Even largely apolitical poet Fernando Pessoa welcomes the coup.

Unfortunately the military then fall out among themselves. The splits between pro and anti monarchists and pro and anti church factions persisted, and led to several changes in leadership.

1928 Carmona presidency and first appearance of Salazar

General Carmona is elected President, appointing a republican colonel as Prime Minister. This combination was marginally more stable, balancing authoritarian and republican factions at the expense of the monarchists.

To sort out the country's massive government debt problem, Carmona appoints a civilian Minister of Finance. Enter University of Coimbra economics Professor Antonio de Oliveira Salazar.

1928 to 1930 Salazar sorts out Portugal's financial crisis

Salazar demanded and got complete control over the expenditure of all government departments, including the military. Launching a fierce austerity program and boosting tax collection, he rapidly got the state budget into surplus, and negotiates better deals foreign lenders. This puts Portugal is a better position to weather the global stock market crash in 1929.

In 1930 Salazar is also appointed as Minister of the Colonies. This position allowed him to get colonial expenditure under control. But it also showed his ruthlessness - foced labour in the colonies was not abolished, but if anything expanded.

1932 Salazar appointed Prime Minister

By now Salazar had become the leading civilian figure in the regime, with the military still prone to faction fighting under a succession of military Prime Ministers. Salazar has repeatedly laid out his plans for a new more authoritarian constitution. In July 1932 Carmona appoints him Prime Minister, with the remit to take this forward.

1933 New Portuguese constitution creates Estado Novo (New State)

The Estado Novo (New State) xxx

1935 Batepá massacre in São Tomé

Possibly hundreds of the islands creoles were massacred by panicking Portuguese colonial authorities and local landowners, who feared a Communist rebellion. The creoles (people of mixed race) were protesting over fears that they were about to be dispossessed of their land or subject to forced labour. The Portuguese governor was promoted rather than prosecuted when he returned to Portugal.

1936 Death camp established at Tarrafal

A new penal colony with a deliberately harsh regime is set up at Tarrafal on Santiago island in Cabo Verde. This became the main prison camp during the dictatorship period for those Portuguese political prisoners and mutineers the regime considered the most intractable.

A known 36 prisoners died from overwork and medical neglect before the camp was closed in 1954. It was re-opened in 1961 for African prisoners once the colonial wars started. (I've been unable to find any information about their survival rate. Some Angolan musicians were sent to Tarrafal)

Though an obvious crime of the Salazarist regime, there was a notable difference in scale from the mass killings over the border in Franco-ist Spain during this period.

Portugal in the Second World War

1951 Portuguese colonies rebranded as overseas provinces

The constitution is altered so the colonies in Africa are renamed as Overseas Provinces (províncias ultramarinas) of Portugal. This is to dodge anti-colonial pressure. It's not an empire - just a very big, multi-racial, "pluricontinental" country. The theme is taken up in all the regime's propaganda. But the UN, the US, the USSR and many of Portugal's African subject don't seem to buy it.

Portugal's Vietnam

1961 War breaks out in Angola

Mozambique and Portuguese Guinea (Guinea-Bissau and Cabo Verde) soon follow. These colonial wars, Portugal's Vietnam, were to drag on until the Revolution of 1974 put a stop to them.

Adriano Correia de Oliveira Zeca Afonso "Menina dos olhos tristes"

Adriano Correia de Oliveira sings composer Zeca Afonso's "Menina dos olhos tristes" (Girl with the sad eyes)

The words are an earlier anti-war poem by Reinaldo Ferreira. For more about the song, other versions (because it is much covered) and Zeca Afonso, a major figure in Portuguese music and 1974 Revolution, see The life of Dr José Zeca Afonso on this site.

1961 India annexes Goa by force

After years of attempting a negotiated settlement, in December the Indian government send in the military to take Goa by force. Goa has been Portugal's main base in the region for 450 years. Salazar unrealistically orders the Portuguese garrison to "fight to the last man". The Portuguese commander puts up a stiff fight, but in order to reduce casualties both military and civilian, eventually surrenders. 30 Portuguese and 22 Indians had been killed. Also annexed by conquest are Daman and Diu, two smaller Portuguese enclaves next to the Indian state of Gujarat on the Arabian sea.

Back in Portugal the commander, Governor Manuel António Vassalo e Silva, and a dozen other officers are disgraced and dismissed from the military. This action may have had consequences later. Officers fighting in the increasingly unwinnable African wars in the 1970s were aware they could get the blame for failing to carry out unrealistic orders from Lisbon. Rather than making them more loyal to the regime, this may have helped politicise them.

1968 Salazar replaced by Caetano

After a bizarre accident falling off a deck chair, Salazar has a stroke. His mental faculties never recover. He is replaced by Marcello Caetano.

1970 Death of Salazar

1974 General António de Spínola publishes book critical of war strategy

Portugal e o futuro (Portugal and the future) came out at the beginning of the year and caused an immediate stir. Spínola was military governor of Portuguese Guinea (now called Guinea-Bissau) between 1968 and 1973, and high in the military councils of the regime. But he had come to the conclusion that the wars in Africa were mostly unwinnable.

This was certainly the case in Guinea-Bissau, where he spoke with the greatest authority. The rebels were well organised and could count on the support of the two neighbouring states, Senegal and Guinea, both former French colonies but long independent (1960 and 1958 respectively). Spinola had even tried attacking across the border, but this just risked widening the war, already fought in four territories (the fourth was Portuguese Timor in Asia)

In Cape Verde Portugal remained in control, but the population was spread over nine islands and easily cut off from any outside support. Cape Verde was administered by the Portuguese from Guinea-Bissau, and had the same independence movement, the PAIGC (Partido Africano para a Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde, led by Amilcar Cabral).

By the 1970s Portugal was losing its grip on parts of Mozambique, especially in the North, despite heavy investment. But there was some chance that Portugal might hang on to Angola, where the rebels were disunited, there was a large settler population and Portugal had assistance from a neighbouring power - South Africa and South-African controlled South-West Africa (now Namibia).

Spínola advocated changing tack and seeking a political solution. Plebiscites should be held in all the teritories, with Portugal offering membership in what he conceived of as a sort of British-style commonwealth. Some territories like Guinea-Bissau might be lost, but they would be anyway. Portugal should concentrate on winning over more of the African population, and concentrating its resources on the territories where they might have an effect.

Spínola was not an advocate of the end of empire. Rather he was seeking to modernise and sustain it in the only way he thought possible. But he had said the unthinkable, and was immediately dismissed and the book banned. But it was published in Brazil and widely read anyway.

Fall of the dictatorship

1974 Carnation Revolution

Led by junior officers, the Armed Forces Movement overthrows Caetano, ending over 40 years of dictatorship. Pending elections, General Antonio Ribeiro de Spinola becomes president.

Portugal after the Revolution

Meta: about this post

This article is still being worked on, so it's a (very long) stub. It needs more details about the Moors, Reconquest and early Christian kings, Terramoto and Pombal, Napoleonic invasion, the loss of Brazil, subsequent Portuguese civil war, British ultimatum of 1890, Portugal in World War II, and more about what happened after the 1974 Revolution.

I also need to find some more music and images (copyright permitting). And what tense should a timeline be in? This one keeps switching from present to past and back. But I thought it worth including this page as it stands because it provides essential background to the music. Re sources, I will eventually do a separate post reviewing the most useful I've found.

Footnotes

Good Article about Portuguese experience in Flanders in the First World War ↩︎

Your thoughts are welcome. Comments powered by Talkyard.