Amália Rodrigues (full name Amália da Piedade Rebordão Rodrigues) is the paradigmatic singer of Lisbon Fado. More than 100 years after her birth she still deeply influences many performers today.

Her voice has a fluent, flexible quality and is also very clear, allowing her to do full justice to the meaning and poetry of the words she is singing.

During her life (1920 to 1999) Amália was at various times heaped with recognition and awards. But at other times, especially in Portugal itself, she was the subject of controversy, hostility and - for a period after the 1974 Revolution, neglect.

Attitudes to Amália mirror those to Fado music generally, which I write about more elsewhere (see links below this article).

But in this post I want to concentrate on what she actually sounds like. For Amália's work lives on in sound recordings and film clips, many now readily accessible, especially from the later period of her career.

Amália Rodrigues "Alfama"

Amália Rodrigues "Alfama" (an old quarter of Lisbon strongly associated with Fado)

Music: Alain Oulman

Words: José Carlos Ary dos Santos

Portuguese guitar: Raul Nery

This first appeared on the 1970 album Com que voz. The version above is slightly later, featuring the distinctive tones of Raul Nery on the high-pitched Portuguese Guitar.

What it means: Both Alain Oulman and Ary dos Santos were leftists in the Portuguese political spectrum, skirting what was possible in the declining years of the dictatorship. By this time the Alfama district was sadly neglected - cut off from the sea by big new roads and insecure and crime ridden at night. This is what the start of the song refers to.

The song sounds sad because it is sad. To quote selectively from the first two verses:

When night falls over Lisbon ...

All of Alfama seems like

A house without windows ...Alfama remains shut within ...

Four walls of anxiety...

Closed within her disenchantment

Alfama smells of sad longing (saudade)

Amália was never a political activist, protest singer or intellectual. She was a fadista. But she sang what seemed good to her and what she could get away with. She steered well clear of taking a public position, which would have been rapidly self-terminating in the climate of dictatorsip Portugal. But she still managed to say a lot to those inclined to hear.

The song ends:

Alfama não cheira a fado

Cheira a povo, a solidão,

Cheira a silêncio magoado

Sabe a tristeza com pão.Alfama doesn't smell like Fado

It smells of people, of loneliness,

It smells of hurt silence

It knows the sadness with its bread.Alfama não cheira a fado

Mas não tem outra canção

Alfama não cheira a fado

Mas não tem outra canção.Alfama doesn't smell like Fado

But there is no other song

Alfama doesn't smell like Fado

But there is no other song.

Amália Rodrigues "Estranha forma de vida"

Amália Rodrigues "Estranha forma de vida" (Strange way of life)

Music: Alfredo Marceneiro

Words: Amália Rodrigues

This song first appeared on the landmark 1962 album simple entitled Amália Rodrigues, sometimes reissued as O Busto (the bust) because of the statue head on the vinyl LP's cover.

The music is by Alfredo "Marceneiro" (the cabinet-maker) Duarte (1891-1982), already one of the great figures of 20th century Fado before Amália even started her career. He was indeed a working carpenter as well as a singer and composer, and connects Amália to the earlier Fado tradition. The words are by Amália herself.

What it's about: Having too much empathy!

Here are two verses (to stay within fair use copyright limits), with English translation.

Foi por vontade de Deus

Que eu vivo nesta ansiedade.

Que todos os ais são meus,

Que é toda a minha saudade.

Foi por vontade de Deus.It was by the will of God

That I live in this anxiety

That all woes are mine

That all are my saudade ¶

By the will of God.Coração independente

Coração que não comando

Vive perdido entre a gente

Teimosamente sangrando

Coração independente.Independent heart

Heart that I don't command

Living lost among the people

Stubbornly bleeding

Independent heart.

¶ Saudade = resigned sadness, longing, pining.

See Top Portuguese song words on this site.

In the O Busto album the mature Amália - entering her 40s at the start of the 1960s, gets to grips with her artform and tackles more challenging material. This was not about explicit politics, but dealing with stronger feelings and some of people's actual experiences.

"Estranha forma de vida" are the only lyrics by Amália on the album. All the others were by serious recognised Portuguese poets active at the time: Pedro Homem de Mello (1904 to 1984), Luiz de Macedo (1925 to 1987) and university professor David Mourão-Ferreira (1927 to 1996) who contributed to the most tracks.

O Busto was also Amália's first musical collaboration with the composer Alain Oulman, who would go on to be involved in what many today consider much of Amália's best work.

The O Busto album was a key step for Amália. She was both pioneering new material for Fado, but also taking the music back into the serious territory it had vacated in the 1920s and 30s in the face of censorship and repression. Perhaps only Amália could have done this, with the greater latitude she enjoyed as an international figure and financial asset to her country.

Amália Rodrigues "Com que voz"

Amália Rodrigues "Com que Voz" (With what voice?)

Music: Alain Oulman (1970)

Lyrics: Luís de Camões (c. 1524 to 1580)

Amália's interpretations often have an epic, weighty feel lifting the emotions she is dealing with beyond the everyday to their full significance in a person's life. This recognition and honouring of emotion is a central characteristic of Fado, and Amália's ability and authority here is what makes her the ideal Fado singer.

The words of this song predate Fado, which arose in 1820s Lisbon, by several centuries. Amàlia responded to often fierce attacks on Fado in Portugal for its triviality and tawdry morality by putting the words of some the countries most respected poets to music and singing them Fado style.

You can't get bigger than Camões when it comes to official reputation, elevated by both Salazar and governments of the modern democratic era. This song is a particularly bold choice, as Camões refers to his stay in prison - which was not just metaphor but a literal fact of his eventful life. In fact he was imprisoned twice - for fighting and for debt.

What it means: With what voice will I cry my sad fate?

Here are the words in Portuguese of the original poem, as given at Wikisource.

Com que voz chorarei meu triste fado,

que em tão dura prisão me sepultou,

que mor não seja a dor que me deixou

o tempo, de meu bem desenganado?Mas chorar não se estima neste estado,

onde suspirar nunca aproveitou;

triste quero viver,

pois se mudou em tristeza

a alegria do passado.Assi a vida passo descontente,

ao som nesta prisão do grilhão duro

que lastima o pé que o sofre e sente!De tanto mal a causa é amor puro,

devido a quem de mi tenho ausente

por quem a vida, e bens dela, aventuro.

It's adapted a bit when sung - passion is swapped in for prison in the second line of the first verse, lines and phrases are repeated for emphasis, the third verse is completely cut, and the first verse repeated at the end.

Though this might seem pretty radical, it is all fairly standard practice when adapting poetry to be sung in the Fado style. Mísia does a very similar thing with Fernando Pessoa's poem "Autopsicografia", as does Mariza with another Pessoa poem "Há uma musica do Povo".

Not only does it make a short poem longer, but the text may need such adaptations simply because it is being presented in a different medium. When listening you may need more repetition to help you grasp the flow of images and meaning compared to reading, because unlike reading you can't control the pace yourself.

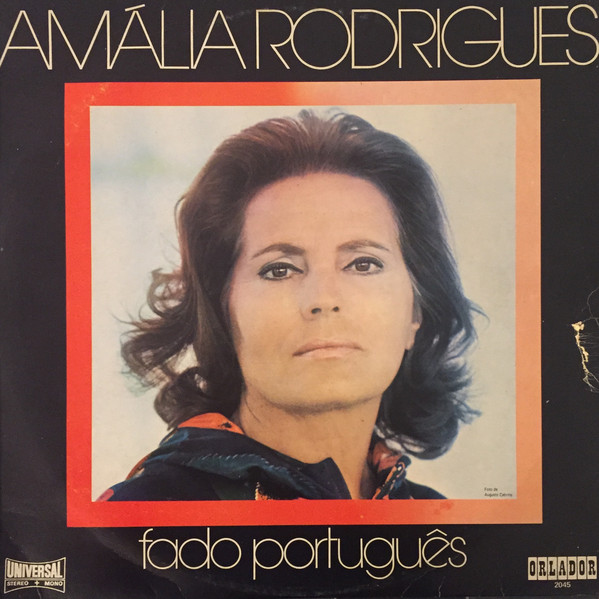

Amália Rodrigues "Fado Português"

Amália Rodrigues "Fado Português" (Portuguese Fado)

(or could mean "the lot of the Portuguese")

Music: Alain Oulman

Words: José Régio

Portuguese guitar: Domingos Camarinha

First appeared as the title track of the 1965 Amália album Fado Português. Interestingly this was distributed internationally first, not appearing in Portugal itself until 1970. By the sixties Amália was an international star, with a larger market outside an austerity-dominated Portugal.

What is means: It's about the supposed origin of Fado on the fragile sailing ships of old. In the perilous calms two sailors remember their homeland, mothers and sweathearts. For example, here's verse four.

Mãe, adeus. Adeus, Maria.

Guarda bem no teu sentido

Que aqui te faço uma jura:

Que ou te levo à sacristia,

Ou foi Deus que foi servido

dar-me no mar sepultura.Goodbye mother, goodbye Maria.

Keep this well in mind

That here I make to you this vow:

Either I will take you to the altar,

or God has given me to a watery grave.

Amália Rodrigues "Foi Deus"

Amália Rodrigues "Foi Deus" (It was God)

Music and words: Alberto Fialho Janes

Foi Deus is a genuine Fado classic, most associated now with Amália Rodrigues but dating back to an earlier period and recorded in numerous versions over the years. Amália's version appeared on the 1955 album Amália Encores, with an earlier appearance possibly in 1952. The words list many things in the world that God made, including the voice that the singer is using and the fate that she suffers.

The life of Amália Rodrigues (23 July 1920 - 6 October 1999)

Fado singer, lyricist and actress, worldwide emblem of Portugal

As she was growing up in the 1920s and 30s Fado was under strong attack from the Right. But she came of age at just the right time to a benefit from a change of tack by the dictatorial regime of Antonio de Oliveira Salazar.

After World War II, the two Iberian dictatorships in Portugal and Spain found themselves in an anomalous position. They were now in a western alliance that loudly espoused democratic values and publicly expressed scorn and horror at anything associated with fascism. It was time to drop the right arm salutes and bad mouthing of democracy, and craft a more friendly image - at least for foreign consumption.

Salazar decided to promote Fado internationally as a more acceptable, welcoming emblem of Portugal and Portugueseness. Franco had already shown the way with the promotion of a tourist-friendly cleaned-up version of Flamenco - which like Fado had also previously been condemned by Iberian rightists for its alleged moral failings and criminal associations.

Earnings dollars was also probably not far from Salazar's mind - he was originally finance minister before rising to supreme power. Neutral Portugal had done well out of World War II, shipping war materials to both sides, and needed to find new sources of foreign currency now this bounty had ended.

Wittingly or unwittingly, Amália became the face of this state-backed campaign. Post war she starred in well supported films, and unlike most other Portuguese was encouraged to travel widely, to promote her records and films. She was, to put it bluntly, an asset to the regime. An obvious and high-profile one in both financial and PR terms.

After the Revolution in Portugal in 1974 to 1975, this caused her some trouble. Both Amália and Fado more generally came under verbal attack. Amália herself stayed abroad for some time. She then released versions of some revolutionary songs, such as Grandola Vila Moreno. Musically there not much that even the greatest fadista can bring to this song (which is now a kind of singalong anthem but derived from a rural male choral tradition), but she needed to show whose side she was on.

But it did the trick and by 1980 she was back in official favour and even honoured by the new democratic government. But her support was not always welcome on the left, and by those who had suffered at the hands of a regime that had often fêted her. And by the 1980s the Portuguese public had fallen out of love with Fado, fascinated instead by the flood of commercial Rock and Pop music the fall of the dictatorship had allowed in from abroad.

Much more recently it has become fashionable to argue that Amália secretly supported the opposition to the dictatorship, even giving the Communist Party or some other revolutionary group money. By their nature and the circumstances of the times such claims are hard to prove.

In her work she certainly formed strong professional relationships with significant leftist musicians and poets, as is clear from some of the examples included here.

But attempts to turn her into an underground conspirator or modern-style celebrity activist misunderstand both Amália and the reality of living under a 20th century dictatorship with an effective police force.

The dictatorship of Salazar and later Marcelo Caetano was engaged in an increasingly desperate colonial war, and was quite prepared to imprison or assassinate its enemies. Despite the cuddly image projected to tourists and its NATO allies, opposition to the regime was not tolerated. Dissidents had to worry about more than themselves. If the feared secret police PIDE couldn't get you they might go after your friends and family to bring you back into line.

Amália didn't sing anti-war songs or openly challenge the regime. She wasn't Zeca Afonso or even Alain Oulman, intellectually committed to a cause and prepared to go into exile or prison. She was a woman of her time, born in 1920, Catholic and Portuguese. Which means not very assertive - listen to the lyrics of her songs!

Like most Portuguese, she was a subject of the dictatorship. She did what she could within the sphere of freedom that she was allowed. She had greater freedom than most Portuguese, but it had its limits.

Amália was an actress, a lyricist and above a great singer. Amália's reputation wasn't fully restored in the land of her birth until the Fado revival of the early 1990s. At that time artists such as Mísia, Paulo Bragança and Dulce Pontes starting going back into Amália's vast repertoire and performing and recording her songs. And they became popular again.

Amália's service to Portugal and the world then became clear. It ran deeper than politics. Amália's real achievement was to save some of spirit of original pre-war, pre-dictatorship Fado and successfully transmit this unique music into the present day. To keep it alive and give it a chance to grow, despite all its detractors.

See also on this site

Who are some of the greatest interpreters of Portuguese Fado?

Covers some other notable Amália songs and her continuing influence on later performers.

Why do some Portuguese despise Fado?

More about the turbulent history of Fado, and why it has come under severe attack from both Right and Left at different times over the years. Essential for understanding Amália and her world.

Further reading and listening

Good YouTube playlist of Amália Rodrigues songs compiled by Cuca Roseta, one of the best modern performers of classic Lisbon Fado. Her Amália Rodrigues playlist has 16 songs, plus four complete albums at the end of the list. An excellent introduction to Amália's dauntingly large repertoire.

Amália's entry on the music collectors' site Discogs.

Amália biography in English, discography and image gallery at the Museo do Fado, Lisbon. UPDATE: At the time of this update (September 2020) the museum is open again despite Coronavirus measures. Some live events, including some linked to the Amália centenary, are going ahead outside. Others are extending into 2021. If the link above doesn't work go in at the top of the Museo do Fado website and drill into the material you are interested in. You can switch from Portuguese to English using the controls at top right of the page, but the English versions are sometimes abbreviated.

Amalia Centenary micro site Mostly repeats the events programme and links to the Museum site. Has some good pictures of Amália

Your thoughts are welcome. Comments powered by Talkyard.